By the late 1890’s advertisements for Mackintosh’s Toffee were appearing in the Strand Magazine (alongside the Sherlock Holmes stories by Arthur Conan Doyle) and through the early 1900’s one of John Mackintosh’s favourite mediums for publicity was full front page advertisements in the Daily Mail. He spent more on advertising than any other confectionery company of the period, and had great fun planning the next promotion. As his son Harold later wrote, “His idea of advertising was that he was telling good news...there was never absent from his advertising his own sense of kindly fun. It was, in fact, a bit of a lark.”

John Mackintosh, the “Toffee King,” died early in 1920, aged fifty one. He was succeeded as Chairman of the company by his eldest son, Harold (later Viscount Mackintosh of Halifax, who, like his father had a flair for advertising, and was soon to be responsible for a campaign which would bring together one of the most well-known cartoon characters of the time and the world’s most famous confectionery — Old Bill and Mackintosh’s Toffee!

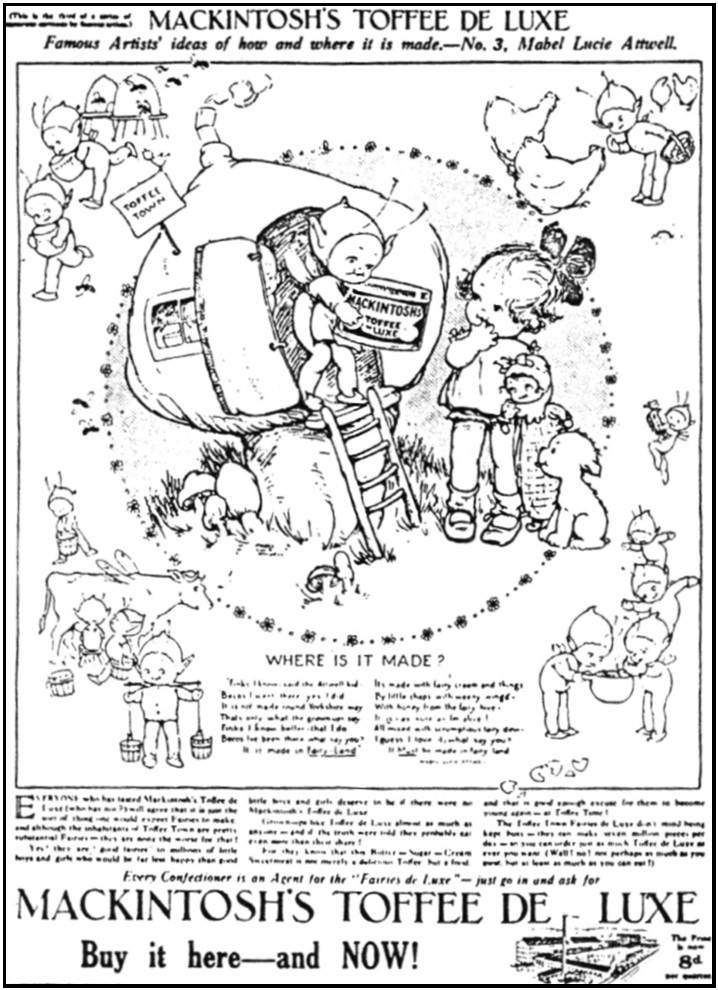

In 1921 Harold Mackintosh decided a new advertising scheme was needed for one of the company’s most established lines, Toffee De Luxe. He came up with the idea of a series of cartoons by famous artists of the day, each depicting their impression of Toffee Town, and his Advertising Agent, E.L. Fletcher was sent to London with orders to commission a number of artists for the job.

In 1890 John Mackintosh, an unknown mill worker from Halifax and his wife Violet, used their entire savings of £100 to open a pastry-cook shop in King Cross Lane, Halifax. Within a year circumstances led John to give up his job at the mill, and concentrate on the business. Little did they realise they were laying the foundation for a company that would become famous the world over for it’s confectionery and see John Mackintosh titled “The Toffee King.”

While their shop sold “pies, buns, jam tarts and Yorkshire cheesecakes,” John Mackintosh soon decided it would be best to concentrate on one speciality—and he chose toffee. Back then toffee was hard and brittle, but the Mackintosh’s wanted to create “something that could blend the crispness of Yorkshire butterscotch with the soft sweetness of caramel.” Violet devised a recipe which gave them the product they were looking for—soon to become known as Mackintosh’s Toffee De Luxe.

John Mackintosh had a flair for advertising from the very start. In those days the toffee trade was reserved to Saturdays, and when their new toffee first appeared in the Halifax shop, he took out an advertisement in the Halifax Courier, offering a free sample the coming Saturday. The following week he placed a second advertisement which read: “On Saturday last you were eating Mackintosh’s toffee at our expense. Next Saturday pay us a visit and eat it at your own expense.” These few short sentences worked, and the public came back again and again to buy the new product.

The result was a series of seven full page advertisements, known as the “Toffee Town Cartoons,” which ran between October 1921 and March 1922. Mackintosh’s spent around £25,000—a huge amount at the time—on the campaign, with the advertisements appearing one a month in the Daily Mail, Daily Express, Daily News, Daily Mirror, Daily Sketch etc, as well as in several of the leading provincial newspapers.

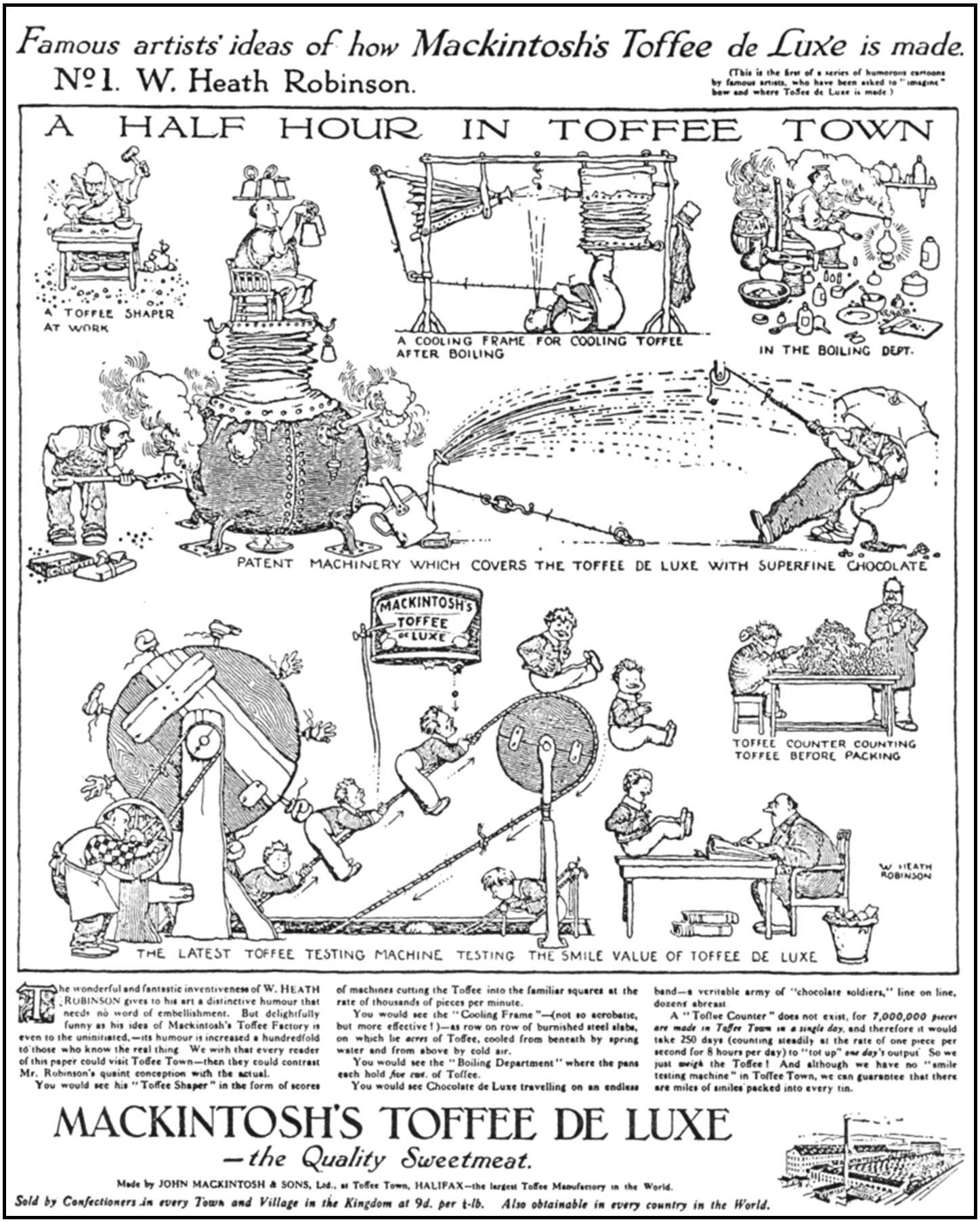

The first advertisement in the series was by Heath Robinson, and as Harold Mackintosh later recalled “was a masterpiece of comic invention. Every time you looked at it you could discover some new flight of exuberant fancy: the shaping of the toffee, as though from marble, with a sculptor’s hammer and chisel; boiling and cooling machines, all working with the precision of their own lunatic logic; and the testing apparatus, which drove along a patched conveyor belt an endless stream of small boys who, as they reached the vital spot, were fed with toffee from a gigantic tin and were finally decanted to the manager’s desk, to be checked and recorded for happy smiles.”

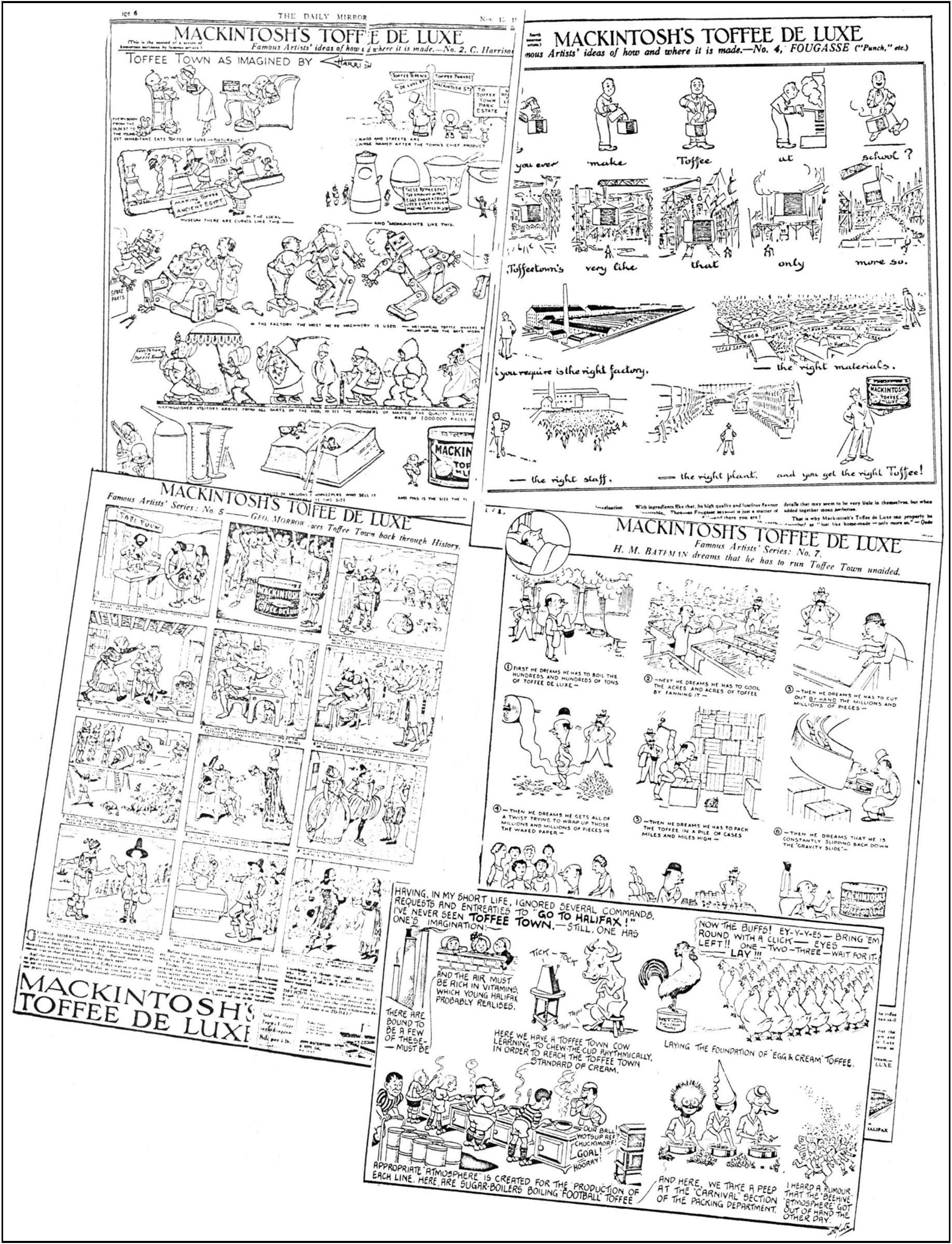

The second cartoon used was by Charles Harrison (a regular contributor to Bruce Bairnsfather’s own weekly Fragments magazine in 1919-20), well known for his prehistoric episodes with a humorous twist. He imagined Toffee Town as being “full of odd signposts and crazy monuments” and had mechanical toffee makers and distinguished visitors from all over the world coming witness the wonder of toffee production. Mabel Lucie Attwell’s contribution to the series was a ‘Fairyland Fantasy’ showing the toffee being “magically produced by a little gnome from his toadstool home.” This advertisement was used as Mackintosh’s Christmas page for 1921, with the added seasonal touch of a personal Christmas message from the Company Chairman. The fourth advertisement was by Fougasse—who had come to the attention of the British public during the First World War, with his distinctive drawings for Punch magazine. He told the toffee story in ‘running commentary’ style—at the time a very original idea as far as advertising was concerned.

Fougasse was followed in the task by George Morrow, another famous Punch artist and “master of delightful historical anachronisms.” Morrow “pictured toffee's progress in episodes from school-book history, including King John’s being bribed to sign the Magna Carta and Catherine Parr finally winning the heart of Henry the Eighth with—guess what? A tin of Mackintosh’s.”

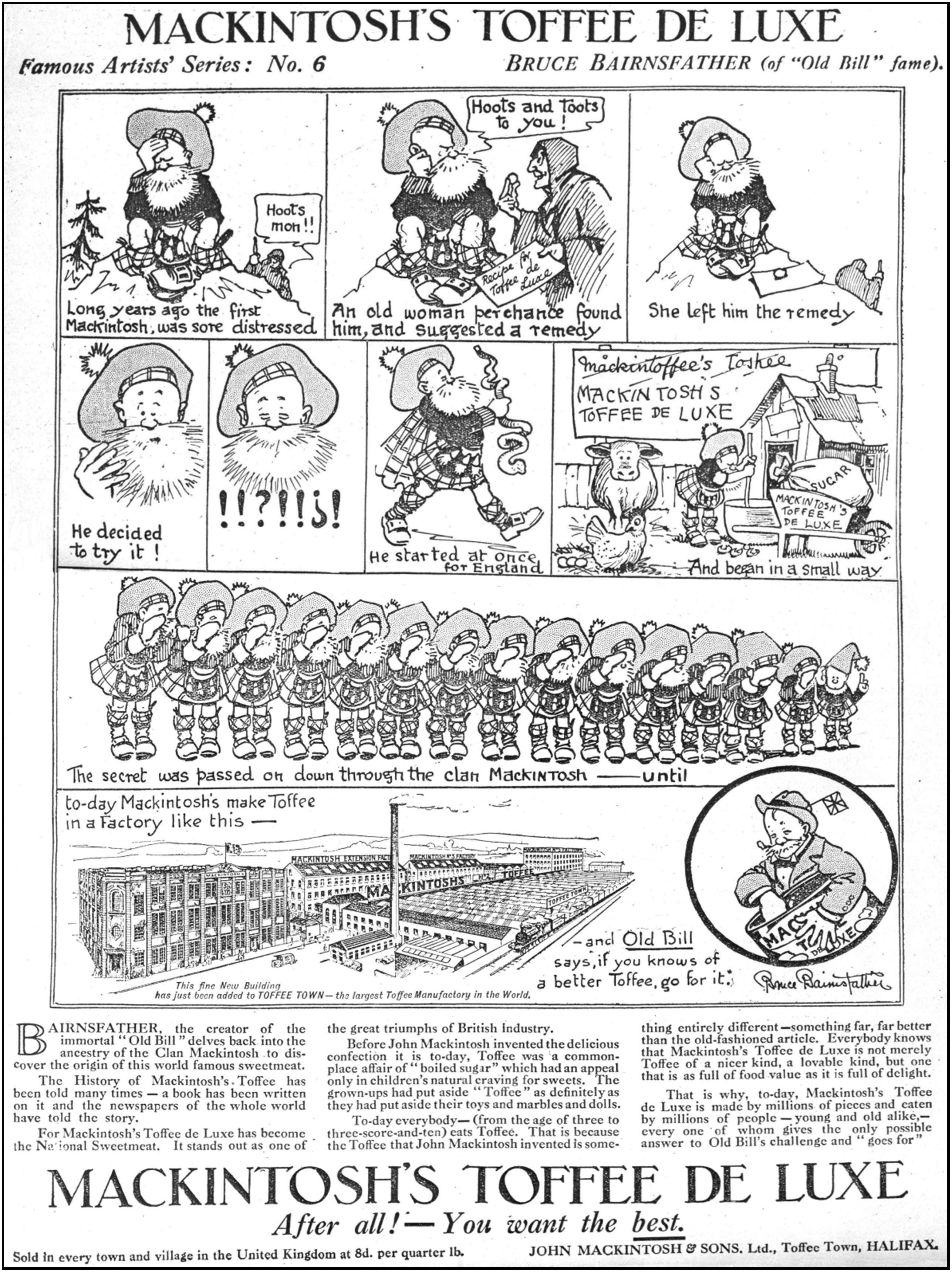

In March 1922 it was Bruce Bairnsfather’s turn to illustrate his impressions of Toffee Town and the story of Mackintosh’s famous Toffee De Luxe. He came up with a ‘history’ of toffee featuring the ‘first Mackintosh’ who was given the recipe and set off for England where he “began in a small way” to produce the famous toffee. “The secret was then passed on down through the clan Mackintosh” (for which BB drew a row of fifteen identical kilted and bearded Scotsmen, each whispering the recipe to the next). The final panel in his drawing declared that “today Mackintosh’s make toffee in a factory like this” - and showed a sketch of Toffee Town, “the largest toffee manufactory in the world.” Old Bill had the final word, clutching a tin of Mackintosh’s Toffee De Luxe and proclaiming “If you knows of a better toffee, go for it.”

The seventh artist enlisted for the campaign was H.M. Bateman, who depicted the “cumulative nightmares” in having to run Toffee Town single-handed—”boiling hundreds of tons of toffee; cooling thousands of acres of it; cutting millions of pieces by hand; wrapping millions and millions of pieces in separate waxed papers, and so on.”

An additional cartoon to the series was provided “free” by W.D. Yates, well-known for his “lively pictures” in the trade publication The Confectionary Journal.

Harold Mackintosh later wrote “this great campaign was my first adventure in advertising and I loved every minute of it.” The Toffee Town Cartoons were also a great success with both the public and the trade, and Mackintosh’s were inundated with requests for reprints. To meet the huge demand the cartoons from the series were reproduced in booklet form and also as a Calendar (presumably for the year 1923). I have never seen or heard of either of these items in any collection, but no doubt examples have survived out there somewhere.

The quotes and illustrations (with the exception of Bruce Bairnsfather’s advertisement) used in this article are taken from By Faith and Work—The Autobiography of The Rt. Hon. The First Viscount Mackintosh of Halifax (1966) and Ad-Ventures with Famous Artists, an article by E.L. Fletcher in Mackintosh’s staff magazine M.C. (December 1953).